Covid 19 information anchoring bias scientific method – COVID-19 information anchoring bias scientific method explores how initial pandemic information, from early reports to official pronouncements, influenced subsequent interpretations and public health decisions. This analysis delves into the scientific method’s application to COVID-19 research, examining the different types of studies and the importance of peer review. It also unpacks misinformation surrounding the pandemic, its connection to anchoring bias, and strategies for combating it.

Finally, it highlights the interaction between bias and the scientific method, emphasizing critical thinking and meta-analysis in evaluating pandemic information.

The pandemic presented unprecedented challenges in disseminating accurate information, while simultaneously exacerbating existing biases and creating fertile ground for misinformation. Understanding these complexities is crucial to navigating future crises and fostering more informed public discourse.

Information Anchoring Bias in COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic presented unprecedented challenges, requiring swift and informed responses. Public health officials, news outlets, and individuals alike struggled to process overwhelming amounts of information, often falling prey to cognitive biases. One such bias, anchoring bias, played a significant role in shaping perceptions and decisions surrounding the pandemic. Anchoring bias describes our tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information we receive (the “anchor”) when evaluating subsequent information.

Figuring out COVID-19 information and anchoring bias using the scientific method can be tricky. It’s easy to get caught up in the whirlwind of news, especially when it comes to things like electric bike prices. For example, checking out the ampler electric bikes price availability can be helpful in understanding market trends and consumer demand. Ultimately, though, we need to remember to critically evaluate all information, especially online, and rely on verifiable scientific data to understand complex issues like COVID-19.

This initial information, whether accurate or not, can disproportionately influence our judgments and actions.Anchoring bias’s impact on COVID-19 information was profound. Early reports, official pronouncements, and even anecdotal accounts served as anchors, influencing how subsequent information was interpreted. For instance, an early estimate of the virus’s contagiousness might have led to over- or underestimation of its true spread, affecting public health measures and individual precautions.

This initial framing significantly shaped public understanding and the development of effective strategies.

Initial Information as Anchors

Early reports and official pronouncements concerning COVID-19, often lacking complete data, acted as initial anchors for subsequent interpretations. The rapid evolution of scientific understanding about the virus meant that initial estimations and predictions, while necessary for immediate action, were frequently revised. This iterative process was crucial for improving pandemic response, but the initial anchors continued to influence the narrative.

Different stakeholders, including government agencies, medical professionals, and news organizations, each presented initial assessments, which in turn shaped public perception.

Influence of Information Sources on Anchoring Bias

| Information Source | Potential Anchoring Effect |

|---|---|

| News Outlets | Early headlines and reports, particularly those emphasizing high mortality rates or rapid spread, could have anchored subsequent public perceptions of the pandemic’s severity and risk. |

| Social Media | Social media’s rapid dissemination of information, often with varying degrees of accuracy, created a fertile ground for anchoring bias. Initial posts and viral rumors could have disproportionately influenced individual beliefs and behaviors. |

| Medical Professionals | Initial assessments of the virus’s transmissibility and severity by medical experts provided anchors that informed public health decisions. Early pronouncements and recommendations could have influenced subsequent strategies and public health measures. |

Impact on Public Health Decisions and Individual Behaviors

Anchoring bias undoubtedly influenced public health decisions and individual behaviors. Initial assessments of the virus’s lethality, transmissibility, and treatment options could have swayed public health strategies, resource allocation, and individual decisions regarding social distancing, mask-wearing, and vaccination. For instance, an initial underestimation of the virus’s contagiousness might have led to insufficient measures, resulting in a wider spread.

Navigating COVID-19 information requires a critical eye, recognizing anchoring bias and applying the scientific method. It’s easy to get caught up in the latest headlines, but understanding how information is presented is crucial. For instance, similar to how a movie’s marketing can influence your expectations, checking out the hunger games prequel movie what you need to know before seeing it can help you separate hype from reality.

Ultimately, we need to be thoughtful consumers of information, regardless of the source, whether it’s a movie or a health crisis.

Scenario: Anchoring Bias in COVID-19 Information

Imagine a news report, early in the pandemic, highlighting a high death rate in a specific region. This initial information (the anchor) could lead to an overestimation of the overall mortality rate. Subsequent reports, even if they provided more accurate data, might be interpreted through the lens of that initial high death rate. Individuals might perceive the risk of infection as significantly higher than it actually was, leading to exaggerated precautions or, conversely, a lack of concern.

This demonstrates how an initial anchor can skew subsequent interpretations of the pandemic’s severity and risk.

Scientific Method in COVID-19 Research

The COVID-19 pandemic presented unprecedented challenges to the global community, demanding rapid responses and innovative research approaches. The scientific method, a cornerstone of scientific inquiry, provided a structured framework for understanding the virus, developing effective treatments, and ultimately mitigating its impact. This framework, though not without limitations, proved crucial in guiding research efforts.The scientific method, a cyclical process, is not just a theoretical concept; it’s a practical tool that allowed researchers to investigate COVID-19 from multiple angles.

From hypothesis formation to data analysis, each step played a vital role in shaping our understanding of the pandemic and developing strategies for control.

Steps of the Scientific Method in COVID-19 Research

The scientific method comprises a series of interconnected steps, each crucial for the progression of knowledge. In the context of COVID-19, these steps were instrumental in accelerating research and development. Observations, for example, from early case reports, helped form initial hypotheses about the virus’s transmission mechanisms and potential impacts. These hypotheses were then rigorously tested through experimentation and data collection.

Subsequent analyses led to refinements in understanding, culminating in the development of vaccines and treatments.

Types of Studies Used in COVID-19 Research

A variety of research approaches were employed to investigate different facets of COVID-19. Observational studies, like those tracking the spread of the virus in specific communities, helped researchers understand the epidemiological patterns. Experimental studies, such as those testing the efficacy of different antiviral drugs, explored potential treatments. Finally, clinical trials, which rigorously evaluated the safety and effectiveness of vaccines, were paramount in developing preventative measures.

Importance of Peer Review in COVID-19 Research

Peer review, a critical component of the scientific method, ensured the quality and rigor of COVID-19 research. Independent experts scrutinized research papers, identifying potential flaws and biases, and validating findings. This process of scrutiny helped maintain the integrity of the scientific record, preventing the dissemination of misinformation and ensuring that only robust and reliable data shaped public health strategies.

Without peer review, the reliability of research findings would be significantly compromised.

Potential Limitations in Applying the Scientific Method to COVID-19

The rapid evolution of the pandemic presented unique challenges to the application of the scientific method. The rapid emergence of new variants, for example, necessitated continuous adjustments to research protocols and hypotheses. The urgent need for rapid responses sometimes prioritized expediency over the meticulousness typically associated with rigorous scientific investigation. Furthermore, ethical considerations, such as informed consent in clinical trials, needed careful navigation.

Examples of Studies Employing the Scientific Method

Numerous studies effectively employed the scientific method to address specific aspects of COVID-19. For example, research on viral transmission dynamics, conducted through epidemiological modeling and observational studies, helped identify high-risk populations and inform public health interventions. Likewise, clinical trials testing different vaccine candidates rigorously assessed their efficacy and safety, ultimately leading to the widespread deployment of effective vaccines.

These examples underscore the crucial role of the scientific method in navigating the pandemic.

COVID-19 Information and Misinformation

The COVID-19 pandemic saw an unprecedented surge in information, both accurate and inaccurate. This flood of data, coupled with the intense emotional toll of the crisis, created fertile ground for misinformation to spread rapidly. Understanding how misinformation spreads and its connection to cognitive biases is crucial for mitigating its impact. The pandemic highlighted the vulnerability of individuals and communities to false or misleading information, impacting public health responses and individual behaviors.Misinformation about COVID-19 spread through various channels, including social media, online forums, and word-of-mouth.

The speed and reach of these platforms enabled the rapid dissemination of false claims, often anchored in pre-existing beliefs or fears. This phenomenon, known as anchoring bias, explains how initial information, even if inaccurate, can influence subsequent perceptions and decisions. Individuals tend to cling to these initial pieces of information, even when presented with contradictory evidence.

Navigating the flood of COVID-19 information can be tricky, especially when anchoring bias sneaks in. It’s crucial to apply the scientific method to assess claims, and critically evaluate sources. This often involves seeking out multiple perspectives. For example, understanding how a smart thermostat like the Nest can optimize energy use, which is similar to the importance of finding various sources to avoid bias when understanding the effects of COVID-19, can teach us how to approach information with a more balanced perspective.

what nest thermostat and why would you want it is a good resource for understanding the technology. Ultimately, applying the scientific method, just like using the latest tech, is key to combating misinformation and making informed decisions about COVID-19.

Misinformation Dissemination and Anchoring Bias

Misinformation thrives in environments where individuals are predisposed to believe certain claims, particularly if those claims reinforce pre-existing anxieties or biases. The anchoring effect plays a significant role in this process. Initial, often inaccurate, information acts as an anchor, making it harder to accept subsequent, accurate information. This is particularly pronounced when the initial information is emotionally charged or resonates with existing beliefs.

Examples of Common COVID-19 Misinformation

Numerous false claims circulated regarding COVID-19, ranging from the effectiveness of unproven treatments to the source of the virus. Some examples include assertions that 5G technology caused the virus, that certain foods or drinks could prevent or cure the disease, and that masks were ineffective or harmful. These false narratives, often shared widely on social media, significantly impacted public perception of the virus, leading to confusion and distrust in official health authorities.

Role of Social Media in Information Dissemination

Social media platforms, designed for rapid communication, became crucial vectors for the spread of both accurate and inaccurate information during the pandemic. The ease of sharing information, combined with the potential for viral dissemination, made these platforms both powerful tools for communication and potent instruments for the spread of misinformation. Algorithms designed to maximize engagement often prioritized sensational or emotionally charged content, further amplifying the reach of false claims.

Identifying and Combating COVID-19 Misinformation

Identifying and combating COVID-19 misinformation requires a multi-pronged approach. Critical thinking skills are essential for evaluating the validity of information. Scrutinizing sources, verifying claims through reputable sources, and seeking multiple perspectives are crucial steps. Additionally, awareness of cognitive biases, such as anchoring bias, can help individuals recognize and resist the influence of misinformation.

Strategies to Combat COVID-19 Misinformation

| Strategy | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Fact-checking initiatives by reputable organizations | Provide accurate information, build trust, and counter false claims. | Can be slow to respond to emerging misinformation, may not reach all affected audiences. |

| Media literacy programs | Equip individuals with skills to evaluate information critically, promoting media literacy. | Requires significant investment in education, may not reach those most susceptible to misinformation. |

| Social media campaigns by health authorities | Rapid dissemination of accurate information, potentially reaching large audiences. | May be ineffective if not presented compellingly, may not counter established misinformation narratives. |

| Community engagement and public dialogue | Promote trust and foster critical thinking through conversations. | May not reach individuals who are already entrenched in misinformation. |

The Interaction of Bias and the Scientific Method: Covid 19 Information Anchoring Bias Scientific Method

Our understanding of COVID-19 has been shaped by a complex interplay of scientific advancements and human biases. The scientific method, designed to minimize bias, relies on rigorous observation, experimentation, and analysis. However, individuals and institutions can introduce biases into the process, impacting the interpretation and application of scientific findings. Understanding these biases is crucial for evaluating COVID-19 information and ensuring evidence-based decision-making.The interplay between anchoring bias and the scientific method can lead to misinterpretations of scientific findings, particularly in a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Initial reports, often acting as anchors, can shape subsequent analyses and conclusions, potentially overshadowing emerging evidence. This can manifest in the overemphasis on early findings, even when later studies contradict or refine them. Critical thinking is essential to counter these biases and maintain a nuanced understanding of the situation.

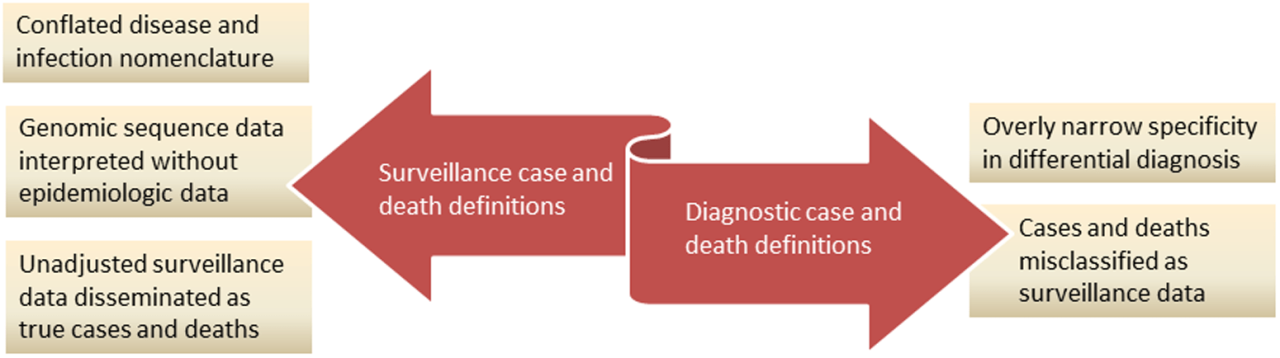

Impact of Anchoring Bias on Scientific Interpretation

Anchoring bias, the tendency to rely heavily on the first piece of information encountered (the “anchor”), can significantly affect how scientific findings related to COVID-19 are interpreted. This initial information, whether accurate or inaccurate, can unduly influence subsequent research, analyses, and public perception. For instance, an early estimate of a virus’s mortality rate, if widely publicized, could become an anchor, influencing subsequent risk assessments and public health policies even if later, more comprehensive data contradicts the initial estimate.

Conflicts Between Anchoring Bias and Scientific Method Principles

The scientific method emphasizes the importance of empirical evidence and continuous refinement of knowledge. Anchoring bias directly contradicts these principles by prioritizing initial information over subsequent data. The scientific method strives for objectivity, whereas anchoring bias introduces a subjective element, potentially skewing interpretations and conclusions. This conflict can lead to a delay in adjusting or refining conclusions as new evidence emerges.

Misinterpretations of COVID-19 Findings Due to Anchoring Bias

Early estimates of COVID-19 transmission rates, often based on limited data and initial observations, served as anchors, shaping subsequent modelling and public health interventions. If these initial estimates were inaccurate or incomplete, they could have skewed subsequent policy decisions and public understanding of the virus. For example, if an early model predicted a much higher transmission rate than was ultimately observed, it could have led to more stringent and potentially unnecessary lockdown measures.

Importance of Critical Thinking in Evaluating COVID-19 Information

Critical thinking is essential for evaluating COVID-19 information. Individuals should be equipped to analyze information sources, assess the credibility of data, and consider alternative perspectives. Critical thinking involves questioning assumptions, examining evidence, and avoiding the acceptance of information solely based on its source or initial appeal.

Meta-analysis and Mitigation of Anchoring Bias

Meta-analysis, a statistical technique that combines the results of multiple studies, can play a vital role in mitigating the effects of anchoring bias in the context of COVID-19 research. By pooling data from various studies, meta-analysis can provide a more comprehensive and less biased understanding of the virus’s characteristics and impacts. This approach allows for a more accurate assessment of risk factors, treatments, and potential outcomes, reducing the influence of individual study findings that may be influenced by anchoring bias.

Illustrative Examples

Understanding the interplay of anchoring bias, the scientific method, and misinformation is crucial for navigating complex health issues like the COVID-19 pandemic. These examples illuminate how these factors can influence individual decisions, research, and public perception. Examining real-world scenarios helps us appreciate the complexities and potential pitfalls in addressing such crises.

Anchoring Bias in COVID-19 Safety Decisions, Covid 19 information anchoring bias scientific method

Initial reports about COVID-19’s severity, often emphasizing high mortality rates, can act as anchors for individual risk assessments. A person might perceive the risk of infection as significantly higher than it actually is, based on an initial, alarming statistic. This could lead to over-compliance with safety measures, such as wearing masks in non-crowded environments, or conversely, underestimating the risk and engaging in less cautious behavior.

For example, if a news report highlights a 10% infection rate in a specific population, individuals might overestimate their own personal risk of infection and adopt more stringent preventative measures than necessary, even if the true risk is much lower in their particular circumstances.

A Scientific Method Example in COVID-19 Treatment Evaluation

A study evaluating the efficacy of a new antiviral drug for COVID-19 would follow the scientific method. Researchers would formulate a hypothesis, like “drug X will reduce viral load in patients.” They would design a randomized controlled trial, assigning patients to either a treatment group receiving drug X or a control group receiving a placebo. Data on viral load, recovery time, and adverse effects would be meticulously collected and analyzed.

Statistical methods would be employed to determine if any observed differences between the groups are statistically significant. This process would involve rigorous peer review and replication to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings. For instance, a study might compare the viral load reduction in patients receiving remdesivir (the treatment) to patients receiving a placebo, while meticulously documenting factors such as age, pre-existing conditions, and other potential confounders.

Misinformation Influencing Public Health Decisions

Misinformation about COVID-19, such as false claims about its origin or the effectiveness of unproven treatments, can significantly impact public health decisions. For instance, widespread belief in the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine, despite scientific evidence to the contrary, led to increased use of this medication, potentially diverting resources from proven treatments and increasing the risk of adverse effects. This resulted in a less effective and potentially harmful response to the pandemic.

Another example is the spread of conspiracy theories about the pandemic’s origins, which eroded trust in public health institutions and hindered public health interventions.

Anchoring Bias in COVID-19 News Reporting

A fictional news report might anchor its coverage of COVID-19 statistics on a particularly high number of cases reported in one region. The report might then use this initial statistic to frame subsequent discussions, possibly exaggerating the severity of the situation in other regions or even globally. For instance, if a news report focuses on the alarming rise in cases in a specific city, it might frame subsequent reports on the overall national or global case numbers by comparing them to this initial, high number, thus potentially overstating the true scale of the pandemic.

Reliable vs. Unreliable COVID-19 Information Sources

| Reliable Source | Unreliable Source |

|---|---|

| Government health agencies (CDC, WHO) | Social media posts with unverified claims |

| Peer-reviewed scientific journals | Websites promoting unproven treatments |

| Reputable news organizations | Blogs with no identifiable author or medical credentials |

| Medical professionals | Influencers promoting health products without scientific evidence |

Reliable sources are characterized by verifiable data, evidence-based claims, and transparency. Conversely, unreliable sources often lack these characteristics, relying on anecdotal evidence, personal opinions, or sensationalized narratives. This table contrasts reliable and unreliable sources of COVID-19 information, highlighting the importance of critical thinking and verifying information from trusted sources.

End of Discussion

In conclusion, COVID-19 information anchoring bias scientific method reveals the significant impact of initial information and biases on pandemic responses. By understanding the scientific method, recognizing misinformation, and cultivating critical thinking, we can better equip ourselves to evaluate and interpret information during future crises. This analysis underscores the importance of rigorous scientific inquiry and the need to combat misinformation in fostering effective and informed public health responses.